A Christmas toast

Seasonal special guest blog, by English Civil Wars novelist Eleanor Swift-Hook. And my 2024 wrap-up.

The dregs of 2024 are oozing out of the door, and I can’t say I’m sorry to see them go. It’s been a year of ups and downs, hasn’t it? So I’m sending my best wishes in this final 2024 newsletter for a New Year of fulfilment, and better times ahead.

My December News

It’s been a quiet few weeks here in Rogers Towers. We had a moment of excitement when it snowed rather prettily and we loved it, till the water supply was cut in the subsequent thaw. But never fear: Severn Trent had matters well in hand, delivering bottled supplies to affected households. We’d have been the better delighted had the supplies arrived in more timely fashion — not till several hours after the mains water was restored the following day.

Saturnalia

December was long a time of midwinter feasting and celebration, even before the Christian era. My third Quintus Valerius novel, The Loyal Centurion, is set during the Roman festival of Saturnalia (17th-23rd December), in York. That other great northern Roman city, Chester, marks Saturnalia with a terrific Roman procession. I wasn’t able to attend, but here are a couple of pictures taken by fellow Roman author Fiona Forsyth this year. Fabulous, isn’t it?

As for my writing news, I’ve been researching like mad for a potential major new project. I’ll have to keep that under wraps for now, but hope to share more concrete news with you in January. Sorry about the vagueness, but that’s publishing for you! Whatever happens, there will be much more Roman Britain suspense and sleuthing to come in 2025. I’ll just mention Viroconium Cornoviorum, and leave you to ponder…

Final guest blog of 2024

To put 2024 to bed in style, I’m delighted to welcome a very special guest, the wonderfully erudite and entertaining Eleanor Swift-Hook. She’s got a suitably celebratory message for us, so I’ll leave her to raise a glass in honour of Christmas and the incoming New Year.

Over to you, Eleanor.

The Battle of Beer and Ale

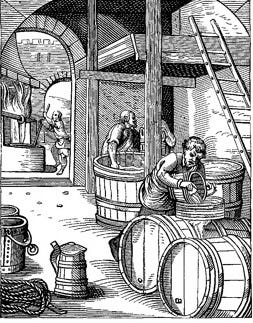

<picture: The Brewer, designed and engraved in the Sixteenth Century, by Jost Amman.>

Today the terms ‘beer’ and ‘ale’ are used pretty much interchangeably in the local pub, but historically they were different beverages and the late 16th and early 17th centuries in England was the time when ale and beer both co-existed and battled for supremacy.

Ale had been the traditional - and nutritious - drink of England just about forever. It was a source of sustenance as much as of hydration and whilst, contrary to popular myth, water was drunk frequently, ale was preferred as being deemed both more healthful and better for the digestion. According to medical belief of the time the stomach was a sort of internal furnace so to drink water would be to put out or subdue that much needed heat. That meant water was not good to drink at mealtimes.

Outside of cities or towns, brewing ale was a job undertaken by women. Sometimes this would have been as part of the domestic duty of a more well-to-do household or sometimes as a commercial enterprise. Alehouses were rife there you could purchase your ale and take it home or sit on a bench outside and be served through a window - or sometimes an inside room might be made available. It was one of the few ways that was acceptable for lone women to earn a living.

But brewing ale was a continual task. The shelf life of brewed ale was, at best, two weeks, so it was a job that had to be done perpetually and year-round.

Ale was made from malt. Malt is grain that is at its peak of readiness to sprout. So malting grain was a process in itself. The well winnowed grain, usually barley, had to be soaked then kept carefully, turning it a lot to ensure it was warm enough throughout and avoided spoiling. You knew your grain was ready to brew when it showed the very first signs of sprouting. Depending on the time of year and the weather this could take two to three weeks.

<picture: malted barley>

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Malt#/media/File:Gr%C3%BCnmalz.jpg

At that point you had to dry the grain to stop it sprouting excessively and keep it at that peak of readiness. That required a warm surface on which the grain could be spread thinly. In summer it might be possible to sun dry, but in winter it would need some form of fire. However whatever fuel was used the smoke would be sure to affect the final flavour of your ale. Drying had to be done carefully to avoid scorching the grain.

Finally, you were ready to brew.

Ale of a regular strength needed around ten gallons (45.5 ltrs) of water for thirty five pounds (15.8 kg) of malt . To make stronger ale you just reduced the water by a couple of gallons. The process involved mashing, heating and then flavouring the ‘wort’, as the unfermented liquid was known, with such plants as rosemary, bay or elderflower. After which it would be mixed with yeast kept from the last batch, left to ferment and be ready to drink four or five days later.

A second wort might be produced from the same mash to make a weaker drink called small ale. Which would be less alcoholic but still very nutritious. It would be drunk between meals much as we might have a cup of coffee or tea, and given to children instead of regular ale at mealtimes.

To keep your household in ale you would need to be working on all the different stages of its production pretty much all the time as each batch would take a month to make and last at most two weeks once made.

But although many households into the 17th century still drank ale, especially in the north of England, it had strong competition from beer and was already much in decline.

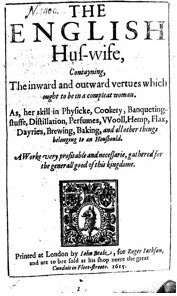

In 1615 when Gervase Markham (1568-1637) published his ‘The English Huswife’ the assumption was that the housewife would be brewing beer and not ale. The key difference between the two being that beer had hops added and ale didn’t.

<picture: The English Huswife>

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_English_Huswife#/media/File:The_English_Hus-wife_1615.jpg

Ale, being made from malt and gently flavoured, was a very sweet drink, but the addition of hops made it less so and introduced a bitterness which many people disliked. However despite this, beer production began to take off in the 16th century and by the 17th had overtaken ale as the favoured drink of England.

But why?

Were tastes changing? Was bitter the new sweet?

Not at all. It wasn't that everyone preferred the flavour of beer, but because the addition of hops meant that the final beverage could last for months not just a week or so. That meant less endless brewing for the housewife and beer could be mass produced, barrelled and shipped for miles around.

This meant that beer was soon made in larger establishments by professional brewers, who were of course men. Ale production remained a domestic and small scale trade, done by women. Although further away from London and the south, ale still remained the staple for many people as hops were not yet plentiful and cheap. As a result whilst both were still drunk in England, by the middle of the 17th century beer was cool and trendy and ale was increasingly something you only drank when there was no beer.

Despite the inexorable march of beer, ale still had its die-hard fans. One was the London water poet, John Taylor (1580-1653) who in 1651 wrote in fulsome praise of ale, and said of beer:

Beere, is a Dutch Boorish Liquor, a thing not knowne in England, till of late dayes an Alien to our Nation, till such time as Hops and Heresies came amongst us.

Another fan was Sir Kenhelm Digby (1603-1665) who lamented the passing of ‘cock ale’.

<picture: Kenhelm Digby>

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kenelm_Digby#/media/File:Sir_Kenelm_Digby_by_Sir_Anthony_Van_Dyck.jpg

First mentioned in a play in 1631, Sir Kenhelm Digby decries how in the 1660s: ‘These are tame days when we have forgotten how to make Cock-Ale’, implying it was a drink he knew was popular in his youth. The recipe he offered wasn’t published until four years after his death.

Cock ale, it seems, was ale which instead of rosemary or juniper, had been flavoured with a well boiled cockeral, four pounds of raisins, two or three nutmegs, three or four flakes of mace and half a pound of dates soaked in two quarts of sack (sack was a fortified wine a bit like sherry).

Let’s just say It would certainly have been a very full-bodied drink!

About the Author:

Eleanor Swift-Hook enjoys the mysteries of history and fell in love with the early Stuart era at university when she re-enacted battles and living history events with the English Civil War Society. Since then, she has had an ongoing fascination with the social, military and political events that unfolded during the Thirty Years’ War and the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. She lives in County Durham and loves writing stories woven into the historical backdrop of those dramatic times.

Her six-book series, Lord’s Legacy, traces the story of Philip Lord, a mercenary commander with a reputation for ruthlessness gained in the wars raging across Europe, who has returned to England at the opening of what will become the First English Civil War. But he returns with a treason charge hanging over his head and in search of his identity and heritage. The truth about that lies in the hands of a mysterious cabal calling itself the Covenant, and their secret conspiracy which began a century before.

Her latest book, The Fugitive’s Sword, opens a new series, Lord’s Learning, set in the 1620s and 1630s against the backdrop of European conflict in the Thirty Years’ War and follows the development of Philip Lord from a boy of fifteen cast alone into those wars to becoming the man we meet in Lord’s Legacy. The second book in the series, The Soldier’s Stand will be released next year.

You can learn more about Eleanor’s writing and the background to her books on her website: eleanorswifthook.com, or follow her on BlueSky @emswifthook.bsky.social or on Twitter/X.

Happy New Year!

[Jacquie’s latest Roman Britain mystery, The Loyal Centurion, is out in paperback and for Kindle. You can follow her on social media, watch her research videos, and find all her blogs and magazine articles at Linktree.]

As I hate bitter and am in fact mildly allergic to hops, give me true ale!

(Minus the poultry, of course. There's a thing called beer can chicken, but I wouldn't want it the other way around.)

Reading Eleanor's excellent exposition on ale and beer made me thirsty. Mine's a pint...