Gold, Irish kings and bog bodies

In search of Romans in the Emerald Isle. Plus guest blog by author Fiona Forsyth

[torc in Nat Mueum, Dublin]

I came back from a research trip to Dublin and beyond, some weeks ago. It was a mixed experience.

That’s not because it wasn’t wonderful, or that I didn’t meet marvellous people, nor soak up the atmosphere of this unique country, nor gain insights to help me draft my fifth Quintus Valerius mystery (working title The Irish Slave). The problem is, I came home with so many unanswered questions.

Before we travelled to Dublin I’d already realised from my literature searches that Irish archaeology of the Iron Age — the period known in the UK as Roman Britain — is only now burgeoning as a research area. I won’t go into why that might be the case; it’s a bit political. Suffice to say that the open, dynamic, self-confident Ireland we enjoyed on this trip is a very different place to my first encounter, back in the 80s.

Witness the brave decision of Fingal County Council to recently buy at considerable expense the promontory of Drumanagh, north of Dublin, now thought to house the remains of a possible Roman trading settlement. We visited Drumanagh and found it accessible and dramatic, though sadly unencumbered by a museum or much in the way of explanatory panels. This was disappointing, as Drumanagh will feature significantly in The Irish Slave, and my academic background won’t allow me to be anything but well-informed. It’s fiction, yes. But as accurate as I can make it.

Published excavation reports from Drumanagh have so far been limited to exploration of a Napoleonic-era Martello tower there. It is known that illegal metal-detectors have in the past removed many artefacts suggestive of a significant RomanoBritish presence here. Longstanding legal action is being waged to return these to public ownership. Digs on nearby Lambay Island have found Roman-style burials of the same period. It is also thought Drumanagh had a direct trackway to Tara of the High Kings, the centre of political and religious authority in the early centuries AD.

We also travelled some dozen or so miles inland to Tara of the High Kings. This will be a key setting in my novel, so again, an important site to explore.

We went there on the sole dry day of our trip, and how glad I was! The views from the Hill of Tara are immeasurable, over the flat green lands of County Meath to the Irish Sea. It’s easy to see why this slight hill was chosen for the High King’s seat, the sacred site of burial of ancestors, and later the inauguration of Ireland’s High Kings. With over 5,000 years of history, the site presented the opposite problem to Drumanagh. It’s such a complex palimpsest, so layered with structures of successive eras layered over each other, that you need the services of an excellent and informed guide. Which we had, in the person of Margaret. She showed us neolithic, Bronze Age and Iron Age (Roman period to me) aspects of Tara. I went away sure that Tara must be central to my book, but pretty hazy about which bits of Tara, and when.

Margaret pointed me to the Tara bookshop, next to the cafe and car park, where we met the remarkable historian and bookseller, Michael Slavin.

Some light began to break. Michael found two essential books for me, his own The Book of Tara, and a pamphlet, Tara, by the late Seán ÓRíordáin of University College Dublin. I thanked Michael, sure we would find out more at the National Archaeology Museum in Dublin on the morrow. He wished me luck, and the following day I discovered why.

What we didn’t find at the National Museum of Ireland

No mention at all, nothing whatsoever, about Drumanagh. A tiny handful of Roman artefacts from Newgrange and Tara, which gave me little contextual information. On enquiry, the museum attendants could tell us nothing about Drumanagh, or Romans, or the Digging Drumanagh project.

Moving on, we were directed to the Tara gallery. Loads there, we were told. And there was — covering everything from 3500 BC, right up to 500 BC. Apparently nothing then occurred at Tara until the 1798 rebellion, and the arrival of freedom fighter Daniel O’Connell in 1843. But, but — the High Kings? Niall of the Nine Hostages? Roman traders? The O’Connors, who were the last kings? Nope, not a thing.

[I did later write to the museum’s Duty Officer, and got a prompt and courteous reply with a list of reference sources to try. All but one were out of print or unobtainable. I did track down one book, borrowed from my go-to source for everything, the Hellenic and Roman Library. In London.]

What we did find in the National Museum

Bog bodies. The most amazing display of sacrificed bodies, complete with a beautifully preserved leather cloak, and even the reconstructed face of one of the unfortunate victims. His fingernails are so well preserved, you can see the perfect manicure. No slaves, these, either, these people. It is thought the bog bodies were young men of the elite classes, even royalty, sacrificed to promote bountiful harvests. It was no sinecure, being upper class in Iron Age Ireland.

You won’t be surprised to hear I’m already planning to insert a bog sacrifice into my book. Call it my homage to the National Museum of Ireland.

[If you’d like to see the video footage of our Irish trip, visit my Youtube channel, and click on The Irish Slave. Apologies for the poor sound quality at times. New videos now available for The Bath Curse, too.)

Guest blog: Fiona Forsyth, author of the Ovid mysteries, including Poetic Justice.

Moving on. Last month I promised you an enticing autumn of guest blogs, from an array of wonderfully talented authors I am lucky enough to call friends. Let’s begin with one of the most erudite and entertaining writers around — in this century or the first (the setting for her mystery series about the poet Ovid). Amazing what those creative types got up to in banishment.

Here’s Fiona to tell us all about writing, Roman-style.

Writing history

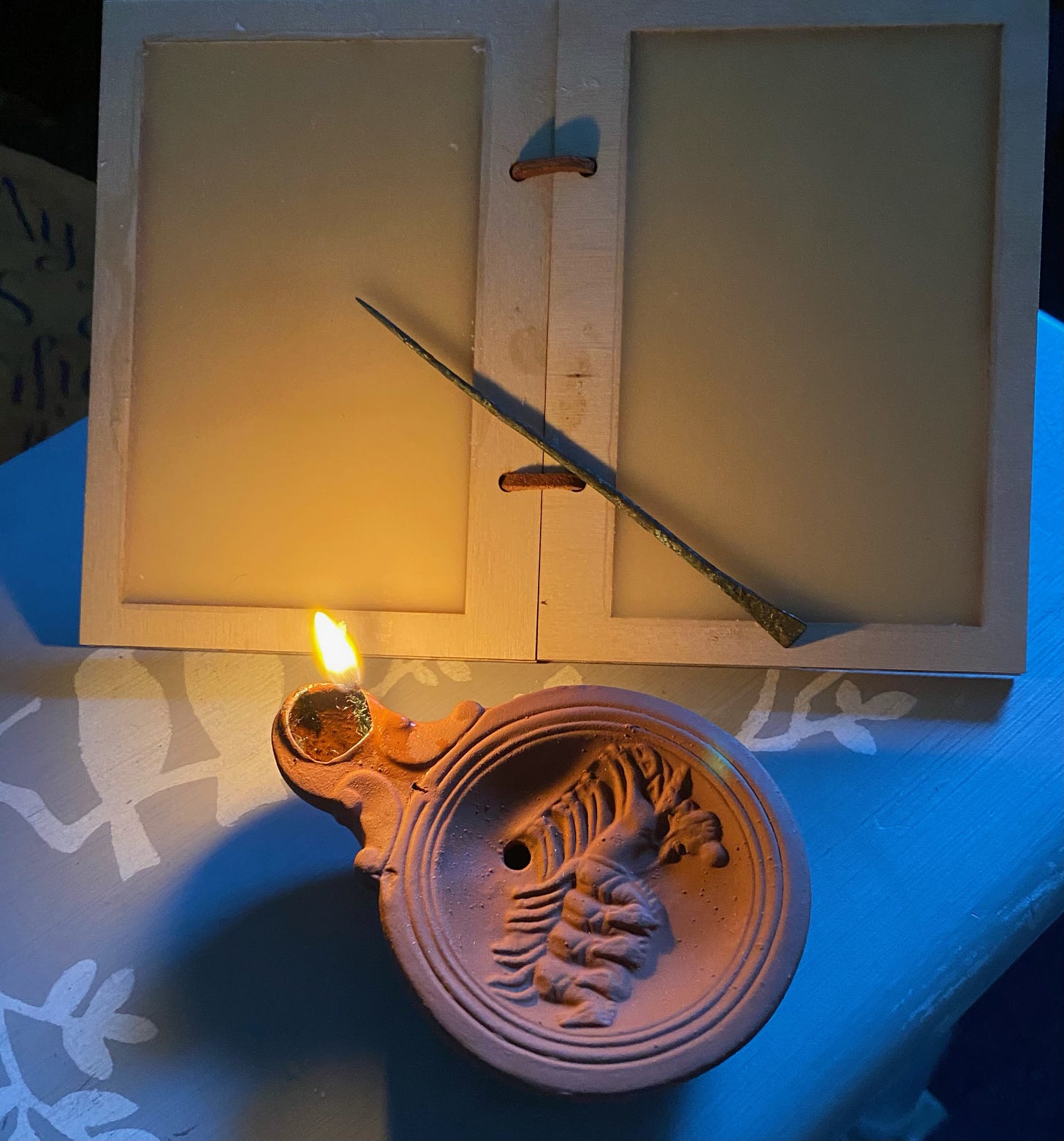

This is a Roman bronze stylus, probably from the first or second century. These pointed pieces of iron or bronze were effectively pens. They were durable, relatively cheap and common so there are hundreds of them in museums all over the world. A stylus was used with wax tablets, carving out notes on a layer of wax laid on a wooden base.

(stylus with a replica wax tablet and oil lamp, ©Fiona Forsyth)

The pointed end scratched into the wax, while the flat end of the stylus could be used to smooth out any mistakes. Carrying a wax tablet and stylus around would have been part of life for household stewards, schoolchildren, accountants and writers.

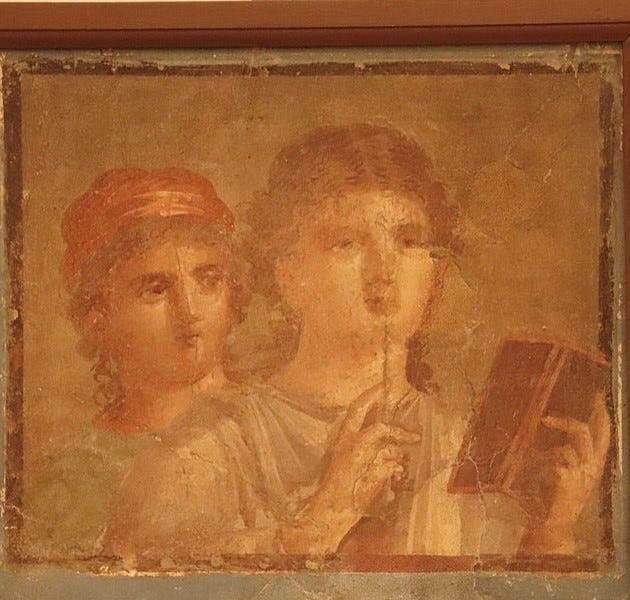

(Pompeii fresco pic – caption Photo courtesy: Following Hadrian, CC BY-SA 2.0 <https:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0>, via Wikimedia Commons)

There is even one depicted in this fresco from Pompeii: from left to right are an ink pot and reed pen, a papyrus scroll and tablets and stylus. The fresco comes from the estate of Julia Felix in Pompeii and is on display in Naples National Archaeological Museum.

What then is so special about my stylus? Well, that it’s mine, for a start. I found it in an antique shop in Chester and before that - who knows what adventures it led? Maybe it was the pen used by a child scratching out the alphabet for the first time, or a centurion picked it up from his desk to work out the work roster for his soldiers. Maybe a luckless squaddie on Hadrian’s Wall was condemned to latrine cleaning by this sliver of bronze.

(The picture of the two girls, no restrictions - caption could be “Hmmm... what to write next?”)

I am particularly interested in the way the Romans wrote things down because writers appear so often in my work. The poet Horace was a major character in my Sestius trilogy, while my new series stars Ovid, the brilliant writer of the Metamorphoses and the Art of Love. He was exiled by the Emperor Augustus in AD8 and spent the rest of his life languishing on the shores of the Black Sea, but he never gave up hope of being recalled. He wrote many poems and letters back to Rome: the final versions would have been copied onto papyrus, but his first drafts would have been made on wax tablets like the one depicted above. I imagine him rolling his favourite stylus between his palms as he gets his thoughts into order and prepares to launch yet another appeal to be restored back to his home and family. His stylus pushes a furrow in the wax and every now and then he stops to blow away the tiny wax grains dislodged by the scratching. As each piece is transferred to papyrus, he warms the wax and smooths out the surface again, ready for his next set of musings.

I didn’t even try to write this article on a wax tablet, not even a few notes. My wax tablets are replicas but my bronze stylus is too precious to risk!

Next month: guest blog by Alistair Forrest; what I’ve been reading recently; writing progress with The Irish Slave.

[Jacquie’s latest Quintus Valerius Roman Britain mystery, The Loyal Centurion, is now available on Amazon, in ebook and paperback. You can follow Jacquie on social media, watch her research videos — including brand-new material filmed in Ireland — and read her magazine articles. All at Linktree.]

I know I've read a series where Agricola taught Tuathal and sent him over to be High King. I doubt this happened. I don't remember who wrote them, they aren't in my library, so I must have read the trilogy in KU.

Looks like there’s work ahead for archaeologists! Isn’t it strange how a good bookshop mysteriously appears just when you need it most?

Many thanks Jacquie.